My New Book, Land Power, is Released Today

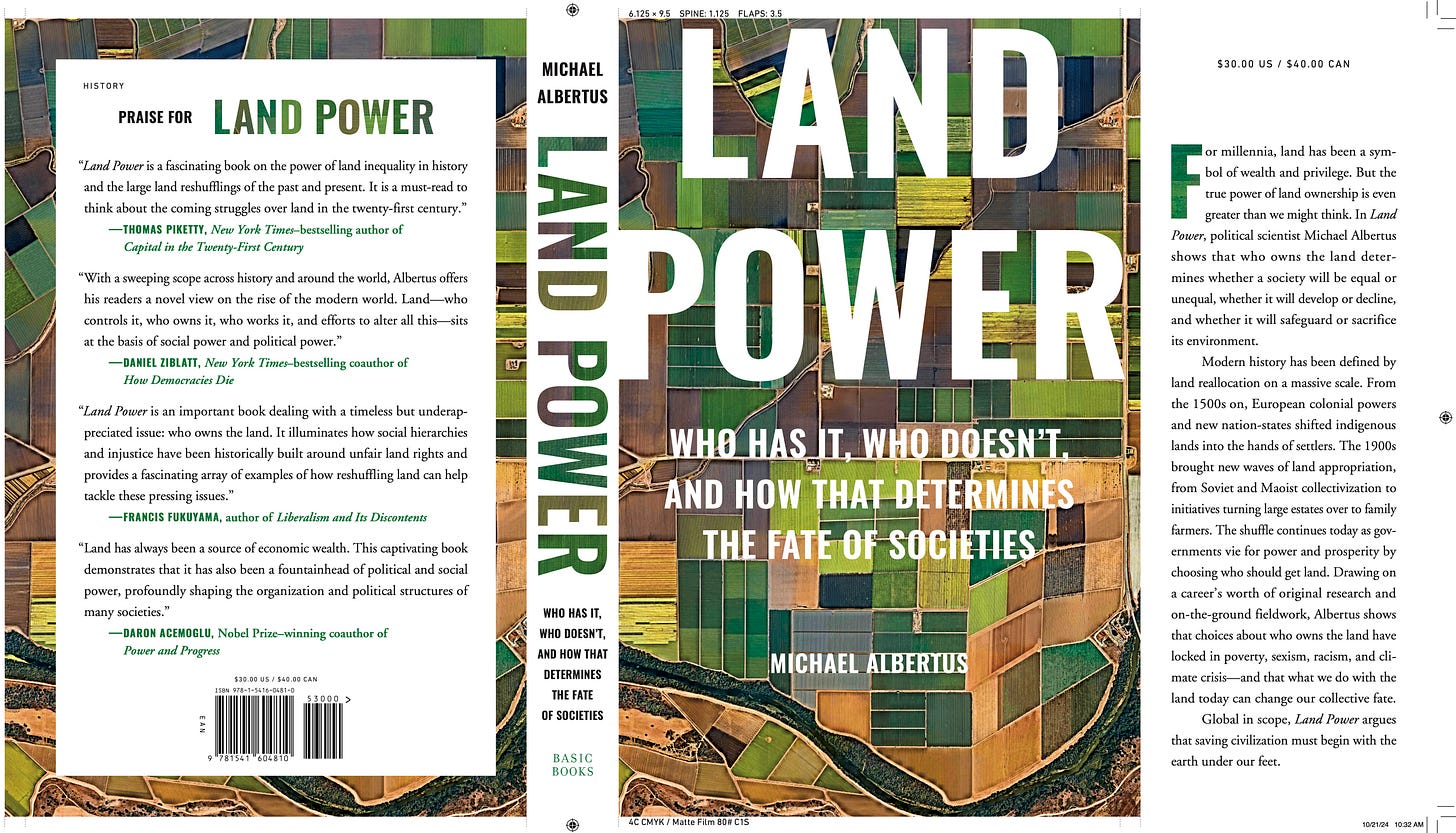

Land Power: Who Has It, Who Doesn't, and How That Determines the Fate of Societies

Today is the official release for my new book, Land Power: Who Has It, Who Doesn’t, and How That Determines the Fate of Societies. Below I share why and how I wrote the book and what I hope you will get from reading it. For those interested in buying it, it’s available in hardback, kindle/eBook, and audiobook from my publisher Basic Books (here), from Amazon (here), from Barnes & Noble (here), and from Tertulia (here). And for those of you who like brick & mortar and local business, please consider asking your favorite nearby independent bookstore to order copies of the book!

Land is power. Our identity, our family pasts, our wealth and well-being, and our relationships are all rooted in the soil beneath our feet.

Many people underestimate how important land is to the way societies work – even long after they urbanize. The biggest problems in societies around the globe today, from racism to gender inequality, environmental degradation, and economic inequality, are deeply rooted in choices about who should get land and how they could use it from just a couple generations ago. Because land is power, those who come to own it come to dominate economic, social, and political power whereas those who lose it or don’t own it become dominated.

Consider the United States, a quintessential settler society. As settlers arrived to colonial America and then pushed west, they displaced indigenous communities en masse. How the country allocated land among settlers and who controlled the land set the stage for a radical experiment in democracy in New England, slavery and the plantation system in the South, and a system of Indian reservations in the West. Today we are living and breathing the consequences of those experiments, from restrictive zoning and unequal housing access in segregated cities to battles over who should control and manage federal land in the West to efforts to restore landscapes and ecosystems that were damaged or destroyed through American settlement and development.

There is an even broader underappreciated history here. As the global population grew over the course of the past several thousand years of human history, land became an increasingly valuable resource. Land came to be an immense accelerator of personal wealth for those who held it. Land ownership came to shape social hierarchy, freedom, and bondage. And it came to mark citizenship and political clout. The choices that societies have made about who owns the land and who doesn’t cut deep ruts across populations and set the stage for trajectories of development, the likelihood that democracy would take root, and patterns of social inclusion or exclusion along lines of race, gender, and class.

This book tells the global story of land over a long sweep of time. I cover a wide range of cases – past, present, and ongoing – to demonstrate the big picture.

It’s hard to overstate how much feudalism, colonialism, and the building of society had concentrated land in places like Europe and Latin America a few centuries ago. By the time of the French Revolution, land battles began to spread across the globe like wildfire. It was the start of what I call the “Great Reshuffle”: the period of upheaval in land ownership over the last two centuries.

In this time period, population growth, state-making, and social conflict have all grown. Demand for land has increased along with the ability of governments to reallocate and reassign it. Land reallocation came to mark nearly every country on earth in fundamental ways. And it set societies on new trajectories. Take for example Russia. Following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the country seized private landholdings and later forged collectives from them that were used in part to support industrialization. It’s hard to conceive of the Soviet Union, the Cold War, and modern Russia without that. The same could be said of China, which reshuffled and collectivized land just after World War II as the Communists took power.

The reshuffle happens in other ways too. The book traces four types of land reshuffling that have defined the Great Reshuffle – settler reforms, collective reforms, cooperative reforms, and land-to-the-tiller reforms – and links them to contemporary patterns of economic development, race relations, the status of the environment, gender relations in countries across the globe. Whether the US, East Asia, Europe, Latin America, or elsewhere, how societies have reshuffled their land has determined the problems they have in these domains.

It’s also very readable!

All of that may sound heady or abstract. But I can promise that the book is an easy – and dare I say, fun – read. The chapters are driven by stories and people. The best thing about writing the book was meeting people and having conversations about their lives and experiences. Their words and their stories feature centrally.

How I wrote the book

Land Power is based on 15 years of work learning about every aspect of the land in dusty archives, vast libraries, countless government land agencies, and through on-the-ground research in fields and furrows from Italy to South Africa, from Ireland to China, and from California to Patagonia. I have spoken with legions of peasants, government officials, land caretakers, and businesspeople who have dedicated their lives to the land and whose trajectories have been shaped by decisions above them to reshuffle, or not to reshuffle, the land.

Writing this book involved a constant back and forth between theory and practice, theory and practice. I had to think through the driving forces behind social change, sift through examples of that change that illustrate these forces, and then reach out to people in all sorts of ways to find compelling personal stories that relay the story I’d like to tell in an immediate and powerful way.

Why I wrote Land Power

I wrote this book to relate an untold story about the power of land in human societies. But I also had another driving motive. Although deep wounds from misused land power of the past haven’t healed, something can still be done about it. Living generations are charged with using land power today to change our world for the better. This book lays out a roadmap for that better future. I share lessons that are being learned today in a wide range of countries grappling with land issues.

Societies around the globe are wrestling with the consequences of past land power. Countries like India and Colombia are trying to increase land access for women in order to rectify their exclusion from land in the past. Countries like Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the US are experimenting with land returns and land co-stewardship as ways to redress the dispossession of indigenous groups from the past. Countries like Chile and Spain are trying to restore environmentally damaged lands from prior exploitative land settlement patterns. All of these are controversial and contested policies that reflect longstanding struggles in these societies.

I also hope that the book caused people to reflect on their own personal and family histories with the land. We are all from the land. Many of us have roots in it that are very deep, even if at times they seem distant.

To learn more

Reading the book will help you better understand, in my view, the deeper roots of contemporary social problems and how we can address them. Here are a few opinion pieces and podcasts I’ve done linked to the book that demonstrate that point – and there will be more coming this week and in the coming weeks!

Bloomberg op-ed: The US Government is Sitting on a Possible Solution to the Housing Crisis

The Hill op-ed: ‘Land politics’ are at the root of our costliest natural disasters

Newsweek op-ed: The Housing Crisis is Really a Land Crisis

Sorry Not Sorry with Alyssa Milano podcast

Praise for the book

I’ve been fortunate to have some brilliant people read early copies of the book, and here’s what a few of them have said:

"Land Power is a fascinating book on the power of land inequality in history and the large land reshufflings of the past and present. It is a must-read to think about the coming struggles over land in the 21st century." --Thomas Piketty, New York Times-bestselling author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century

"With a sweeping scope across history and around the world, Albertus offers his readers a novel view on the rise of the modern world. Land--who controls it, who owns it, who works it, and efforts to alter all this--sits at the basis of social power and political power." --Daniel Ziblatt, New York Times-bestselling coauthor of How Democracies Die

"Land has always been a source of economic wealth. This captivating book demonstrates that it has also been a fountainhead of political and social power, profoundly shaping the organization and political structures of many societies." --Daron Acemoglu, Nobel Prize-winning coauthor of Power and Progress

"Land Power is an important book dealing with a timeless but underappreciated issue: who owns the land. It illuminates how social hierarchies and injustice have been historically built around unfair land rights and provides a fascinating array of examples of how reshuffling land can help tackle these pressing issues." --Francis Fukuyama, author of Liberalism and Its Discontents

"Now more than ever it's essential to talk about land use with the widest lens possible. Land Power offers new insights into how public and private initiatives worldwide can effectively safeguard ecosystems and societies for future generations of all life." --Kristine Tompkins, President and Co-founder of Tompkins Conservation

Thanks David, I'd love to hear your reactions. And your thoughts about how it interacts with the other things you've been reading on US industrialization. That sounds fascinating!

Thank you for this. One thought that emerges is how low-value "waste"/"degraded" land can quickly become sites of habitation and co-stewardship through successional forestry integrated with human life, and through hyperlocal open-loop production of energy and materials. In other words, when a frictionless path forms between "waste" and "abundance", the value equation is inverted and the momentum of history can begin to be disarmed.