Q&A With Election Law Expert Nick Stephanopoulos on Texas Republicans' Extreme Partisan Gerrymander

Why the rare move threatens local representation and the partisan balance in the US House – and could spark widespread partisan redistricting

This post is an interview with Nick Stephanopoulos, who is a professor at Harvard Law School specializing in election law and the author of Aligning Election Law. Nick and I also overlapped for a time at the University of Chicago, and during that time he helped to launch several lawsuits against states engaged in extreme partisan gerrymandering of the type that the Texas legislature is currently engaged in. That is what motivates this post. At President Trump’s urging, Texas has drafted a new map of its congressional districts that explicitly aims to flip five districts to Republicans as the party worries about keeping its narrow majority in the midterms. The nakedly partisan power grab, which seeks to tilt the electoral playing field toward Republicans, has caused Democratic lawmakers in Texas to flee the state to prevent a vote on the new districts. Republicans have reacted by calling on the FBI to find and arrest them. Other states run by Democrats and Republicans are also threatening to redraw their districts in a more heavily partisan fashion, generating a competition over partisan redistricting that could further polarize state politics. Nick is as much an expert as anyone on what this might look like and the legal landscape (and history) of partisan redistricting, so I asked him to weigh in on it. He also posed some questions to me about what this means for the broader landscape of democracy and democratic erosion in the US.

1) What was your role in prior litigation on partisan gerrymandering and what was the ultimate result of that?

It’s a pleasure to join you, Mike, for this very timely Q&A. With respect to partisan gerrymandering, this has long been a focus of my work as a scholar and litigator. Most pertinent here, in 2015, I coauthored an article with political scientist Eric McGhee introducing a new measure of the partisan fairness of district maps, which we called the “efficiency gap.” Around the same time, I helped launch a partisan gerrymandering lawsuit against Wisconsin’s state house plan, which had one of the worst efficiency gaps of any map in modern history. Unlike all prior partisan gerrymandering litigants, we convinced a three-judge federal court to invalidate Wisconsin’s plan. However, this decision was vacated by the Supreme Court on the technical ground that we hadn’t yet proven our plaintiffs’ “standing” (that is, their specific injuries stemming from their districts).

While the Wisconsin case was back in the district court, I joined another partisan gerrymandering lawsuit against North Carolina’s congressional plan. This plan also had one of the worst efficiency gaps of the entire modern era. It was more biased than essentially all computer-generated maps that matched the plan’s performance on nonpartisan criteria, too. We again persuaded a three-judge federal court to strike down the plan. When the state appealed to the Supreme Court, though, the Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering claims are inherently nonjusticiable—not suitable for resolution by federal courts. The Court thus overturned a 1986 precedent that had recognized partisan gerrymandering as a constitutional violation. The Court also rejected one of the classic rationales for judicial intervention: safeguarding the political process from elected officials aiming to entrench themselves in office. I wrote this article after the Court’s decision highlighting how the Court no longer believes in intervening to protect democracy.

2) What is Texas trying to do with their redistricting plan, and why has it garnered so much attention?

Texas is trying to redraw its congressional district plan, in the middle of the decade, solely in order to increase the plan’s pro-Republican tilt. There has long been a norm that district maps are redrawn only once every ten years, after each Census comes out. This norm promotes stability in representation and prevents the endless fine-tuning of maps for the sake of partisan advantage. Texas is shattering this norm, and it’s doing so for no legitimate reason. Unlike in 2003, when Texas also engaged in mid-decade re-redistricting, the plan Texas is now seeking to replace was enacted by the legislature, not imposed by a court. So Texas can’t argue that it wants to substitute a “more” democratic map for a “less” democratic one.

Additionally, the U.S. House is, at present, extremely fair in aggregate. This is true whether the chamber’s bias is measured using seat-vote metrics like the efficiency gap or by comparing enacted plans to party-blind computer-generated maps. So Texas’s mid-decade re-redistricting also can’t be defended on the ground that it would make the U.S. House, as a whole, fairer. To the contrary, a more potent Republican gerrymander in Texas would skew the U.S. House to the right and undo its current balance.

3) Based on the draft maps that the redistricting committee has released, does it seem like Republicans might successfully flip a handful of seats (or at least most of them) in their direction?

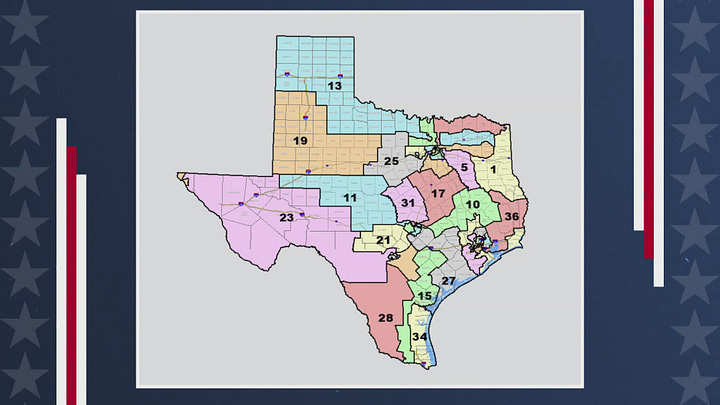

The granular analysis I’ve seen indicates that five districts would be flipped from Democratic to Republican control in the proposed Texas plan. However, two of these five districts haven’t been changed all that much, so it’s possible their Democratic incumbents could hang onto them.

Here’s PlanScore’s analysis of the proposed Texas plan. (PlanScore is a website I’m involved with that provides partisan fairness scores for past and present district plans.) The new Texas plan is projected to have a pro-Republican efficiency gap of about 17%, which translates into more than six extra seats for Republicans relative to a neutral map. By contrast, Texas’s existing plan has exhibited a pro-Republican efficiency gap of just 1%.

4) Other states led by Democrats like California, New York, and Illinois are threatening to counter Texas's redistricting with their own redistricting plans. Is that realistic, or do state laws prevent that in most cases? Might other Republican-led states follow Texas's lead if it is successful?

If Texas opens the Pandora’s box of partisan mid-decade re-redistricting, other states will likely follow suit. Blue states will try to offset Texas’s intensified gerrymander, while red states will try to double-down on Texas’s strategy. As I’ve previously written, I think the imperative with respect to congressional redistricting is national partisan fairness: a U.S. House that’s fair, in aggregate. So I think blue states would be justified in responding to Texas’s mid-decade pro-Republican gerrymander with offsetting pro-Democratic redraws. This certainly isn’t my first-best universe. I’d much rather have fair maps in all states aggregating to a fair U.S. House. But the Supreme Court has refused to police partisan gerrymandering and the current Congress certainly isn’t going to enact sweeping redistricting reform. So in the world we’re stuck in, our options are offsetting gerrymanders in red and blue states or gerrymanders in red states and fair maps in blue states. The former option is much better than the latter, in my view, because it prevents representation and policy nationwide from being distorted by gerrymandering.

Now, it’s true that blue states like California, Colorado, New Jersey, New York, and Washington have enacted reforms (like independent commissions) that make it harder for these states to adopt offsetting gerrymanders. But the key word here is harder—not impossible. These reforms have generally been approved through state constitutional amendments. And just as states constitutions were amended to make redistricting less partisan, they can be amended again to authorize offsetting gerrymanders. Indeed, this appears to be California’s strategy: to get a constitutional amendment passed that would codify a new (more pro-Democratic) congressional plan for the rest of the decade.

5) How does the Texas redistricting proposal relate to the broader use of laws and raw political power on the part of Republicans to entrench their current political advantages at the national level? In your view, how does that impact American democracy?

The Texas gambit isn’t exactly new, as Texas did almost the same thing twenty years ago and reformers have warned for years about the possibility of mid-decade re-redistricting. Aside from its mid-decade timing, the Texas plan is also similar to a number of aggressive gerrymanders we’ve seen over the last few decades. So I wouldn’t say that this situation represents a dark new era in American politics. It’s more like a continuation of a dark period in which we’ve already been living for a generation or more. Now, I do think it’s significant that Republicans in Texas came up with this idea. In my judgment, Republicans have been more willing to try to change election laws for their benefit in recent years, and this incident fits that pattern to a tee. But I also think it’s significant that, unlike in 2003 when Texas last redrew its plan mid-decade, prominent Democrats are now arguing that blue states should fight fire with fire. This is a sign that the era of unilateral disarmament in the redistricting wars may be over. One last glimmer of optimism: You gerrymander when you can’t or won’t resort to even cruder tactics like widespread disenfranchisement or outright election subversion. So the situation in Texas may suggest that fears of the actual demise of American democracy are overblown.

And here are Nick’s questions back at me.

1) One of the themes of the gerrymandering tit-for-tat is federalism. It’s Texas and not the federal government that’s trying to redraw the state’s plan, and it’s California that may respond in kind. How do you think about democratic erosion in a context where states have enormous authority to set electoral policies and federal power is relatively constrained?

Federalism can cut both ways when it comes to democratic erosion or democratic deficits. It’s possible to have authoritarian enclaves embedded within nationally democratic governments. Think of the US South under Jim Crow prior to the Civil Rights movement. That facilitated the mass disenfranchisement of Black Americans. At the same time, federalism makes possible democratic enclaves within a broader environment of authoritarianism at the national level. Whether national-level democracy or local-level democracy – if you can only have one of them – is more important depends on the policy in question.

One troubling aspect of the Texas redistricting plan, in my view, is that it took its cues directly from the federal government (and, by most accounts, it seemed rather unwilling initially). That’s in keeping with a pattern of the Trump administration to try to reach down and into local politics and to break down barriers that had previously held because of prevailing norms.

2) I’ve long thought of gerrymandering as the single most pernicious practice in modern American politics—more capable of yielding misalignment than any other contemporary policy. Do you share this view of gerrymandering? Or do you see it as similar to other tactics (electoral and non-electoral) that politicians often use to consolidate their power?

I do think that gerrymandering strikes many people as fundamentally unfair. After all, you can have exactly the same people casting exactly the same votes, but you get a different outcome because of how the lines are drawn. When they’re being drawn precisely to silence some votes, that strikes people as unfair. And like you say, because that generates different politicians in office, it also generates different policies – ones that can be far from what voters as a whole actually want.

The question of whether gerrymandering is the most pernicious modern practice or trend is a tricky one. It seems like a considerable part of modern misalignment between voters and policy outcomes is due to the disproportionate and distorting influences of money in politics, which can buy politicians and policies (and if you’re Elon Musk, even a hangout in the Oval Office for a few months). Another part comes from the severe mismatch in the wealth, income, and status between voters and politicians. And I also worry a lot right now about erosion in the rule of law (which I’ve written about previously). All of that can move policy – and the ability to enact it – away from what most Americans prefer.

3) The linchpin of my reasoning about the Texas situation is that we need to think about the U.S. House as a whole—not individual congressional plans in isolation. Do you agree with this nationwide perspective, or do you think that partisan fairness (and other democratic values implicated by redistricting) matter more at the level of the congressional delegation?

I certainly agree with the point that the US House as a whole should fairly represent Americans. That’s critical at a moment of real democratic fragility, and one in which politics has become increasingly national. That said, I’m also with you that the best-case scenario is one in which there are fair maps in all states that yield a fair US House rather than having biased maps in the states that aggregate to a nationally fair House. Otherwise I fear we head toward a scenario in which many legislators can’t face or talk to large parts of their constituencies given how poorly they represent them. That doesn’t bode well for local representation and participation.

Leading images are of Nick Stephanopoulos the proposed Congressional districts in Texas. The panned out image masks some of the important changes also impacting district lines in urban areas.